The future of coral reefs

I went scuba diving for the first time in the Seychelles in the Indian Ocean in 2000. At 10-years-old, I was captivated by the beauty of the underwater world and diversity of marine creatures I’d seen but my mum finished the dive having had a very different experience. She had visited the Seychelles ten years previously and was horrified to see how the ecosystem had deteriorated since her last trip. In 1998, the Seychelles was severely impacted by the largest global-scale coral bleaching event of the time. Unusually warm ocean temperatures across all tropical ocean basins caused bleaching followed by 90% coral mortality in many regions, including the Seychelles.

Since that initial event, two further global bleaching events occurred in 2010 and 2016 in addition to numerous smaller-scale bleaching episodes. Over this period, bleaching events have become more frequent ; the number of years between events has decreased from one every 25-30 years in the 1980s to one every 6 years by 2016. Some coral reefs in the Seychelles have not yet returned to their pre-1998 bleaching coral coverage , so this increasing bleaching frequency puts considerable strain on coral reefs’ ability to recover. With further increases in ocean temperatures projected with climate change, coral reefs currently face a very uncertain future.

Coral reefs are made up of tiny reef-building animals known as polyps. These polyps secrete layers of hard calcium carbonate slowly building up complex structures over time. Coral polyps share their tissues with a type of photosynthetic algae. While the coral polyp provides a protected environment for the algae to live in, the algae provides the coral with food and oxygen, and removes the coral’s waste products.

Reef building corals inhabit tropical oceans and are already living at the upper limit of their temperature tolerance. Prolonged increases in ocean temperature cause the relationship between the algae and the coral host to breakdown. The coral polyp then expels the algae from their tissues exposing their white skeleton, hence the term ‘coral bleaching’. If increases in temperature are short-lived, corals are able to regain their symbionts and recover quickly but sustained high temperatures cause corals to die. This frees up space for the colonisation of other organisms such as macro-algae. Coral recovery at this stage is much more difficult.

Coral reefs are extremely ecologically and economically valuable. They are the most biologically diverse marine ecosystems in the world providing a habitat for a range of species from smaller tropical fish and invertebrates to sharks, turtles and rays. They also provide a livelihood for millions of people living in tropical regions. Coral reefs contribute to fishing and tourism industries as well as providing building materials, new medicines and coastal protection from storm damage. These highly valuable ecosystems were estimated to be worth $9.8 trillion annually in 2014. However, numerous threats to coral reefs are causing their area and their value to decline, threatening people’s livelihoods and organisms’ habitats.

Coral reefs are threatened on a local scale by overfishing, the use of destructive fishing techniques, pollution and coastal development. For many years of coral reef research, these local-scale stressors were thought to be the greater threat but this has now shifted and climate change is commonly referred to as the greatest threat to coral reefs. Current approaches to coral reef conservation against climate change focus on local-scale protection. Marine protected areas are set up to prevent all fishing or limit particular fishing practices. It is hoped that reducing the local-scale threats will increase the coral reefs’ resilience to climate change making them better able to cope with changing environmental conditions. However, there is debate as to the effectiveness of this approach.

Though the outlook for coral reefs is poor, there is some good news. Coral reefs in Moorea in French Polynesia have repeatedly recovered to their pre-disturbance coral coverage following multiple bleaching events, tropical cyclones and outbreaks of invasive species. Some coral reefs in the Maldives recovered following the 1998 bleaching event by 2012 and some reefs in the Seychelles were able to recover towards their pre-1998 coral coverage by 2011. However, many of these sites have bleached again in recent years and their recovery from these events are not yet known.

Climate change threatens coral reefs worldwide, no matter how far removed they are from human impacts and this threat is rapidly increasing. Some studies suggest that we focus conservation efforts on the least vulnerable areas as these have the highest chance of survival. To do this, we need to predict where these areas are with greater certainty, we need to know how these ecosystems will respond to the impacts of multiple different local and global threats, and we need to determine the rate at which they can adapt to change.

Coral reef ecosystems are an essential source of food, protection and income for millions of people and their loss will have far-reaching consequences though they’ll be felt much more intensely by some than others. The greatest threat to coral reefs is being caused by everyone responsible for emitting greenhouse gases, myself included. Their conservation is therefore everyone’s responsibility. The most important conservation measure we need to protect coral reefs is to rapidly cut down on our carbon emissions. Without removing the source of the greatest threat, we cannot expect coral reefs to survive.

References

You may be interested in reading about

All articles

2/3/21

An overview on climate sensitivity

Human-induced climate change, driven by increasing emissions of atmospheric greenhouse gases, remains an ever-increasing issue at the centre of climate science whilst also having implications for society, policymakers and governing-bodies.

1/3/21

The energy charter treaty

A new law on climate change and the energy transition is about to come to light in Spain, with the aim of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees and meeting the pledges made by the European Union at the Paris Agreement.

19/1/21

Delhi and the River of Love

As I drove by the bridge on the river Yamuna, it looked calm, serene, and inviting. However, getting closer, the unmistakable smell of decay greeted me. The banks were full of rubbish and the river was black. The stillness of the calm and serene river turned out to be death.

15/6/20

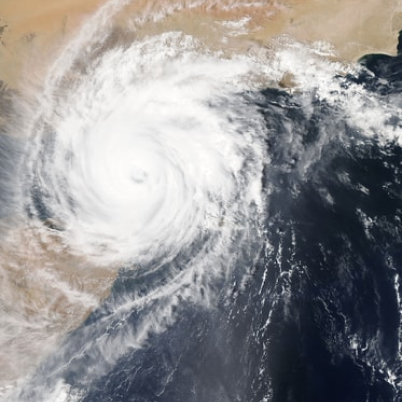

Forecasting tropical cyclones in a changing climate

Most of us engage with weather forecasts when we’re trying to plan our weekends, but they can also help us understand and cope with our rapidly changing climate.